April is when the new fiscal year begins in Japan. If you live in Japan, you might be facing a change and a new phase of life. Speaking of change, the tax rate on sake will decrease beginning this October, and the tax on wine and other fruit liquors will increase proportionately to make it the same percentage. Taxes on sake have undergone various changes in response to the times and circumstances. In this post, we will introduce the history of sake tax fluctuations.

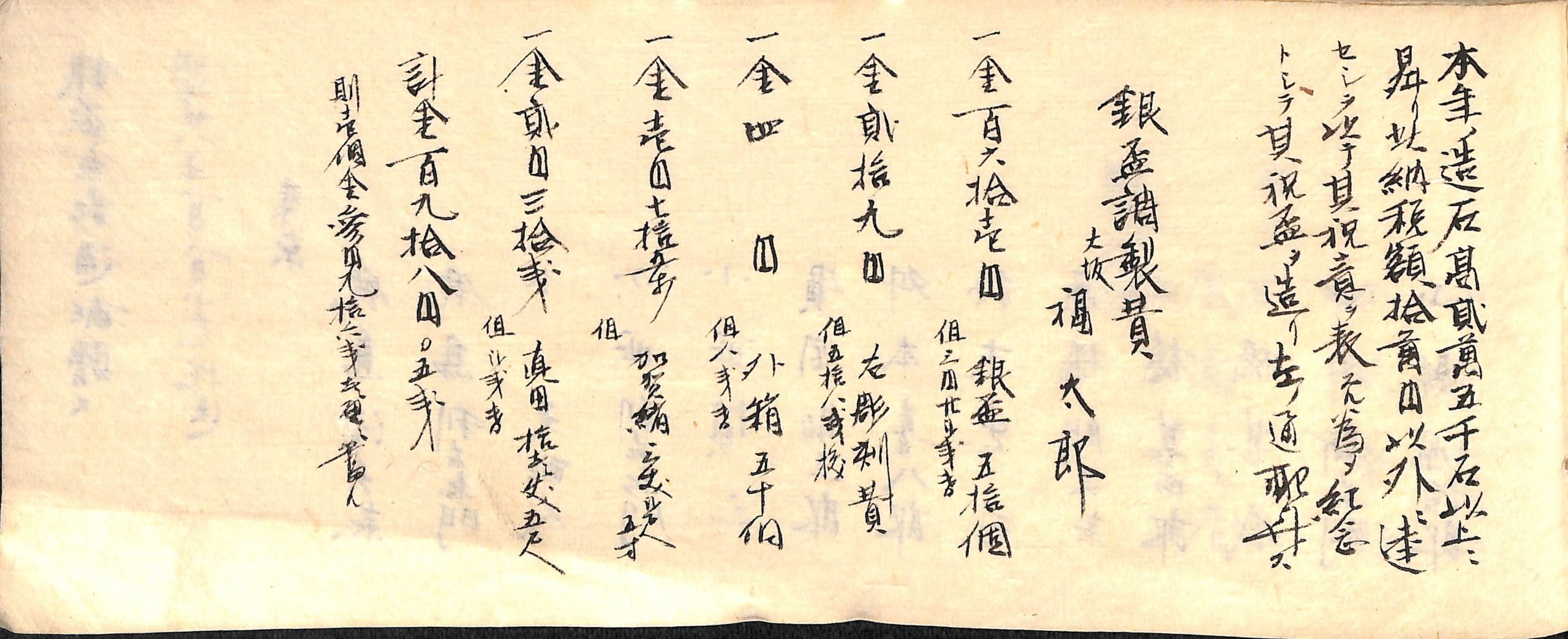

the Tax Payment to 100,000 yen in 1895

The policy of imposing taxes on sake began around the Kamakura and Nanboku-cho periods (12th-14th centuries). It was during that time that sake began to be brewed and sold in various parts of Japan. In the Muromachi period (1336-1573), a tax on sake called “tsubosen” was imposed. (“Tsubosen” literally means “pot money” – referring to the main sake container of the time – pots.)

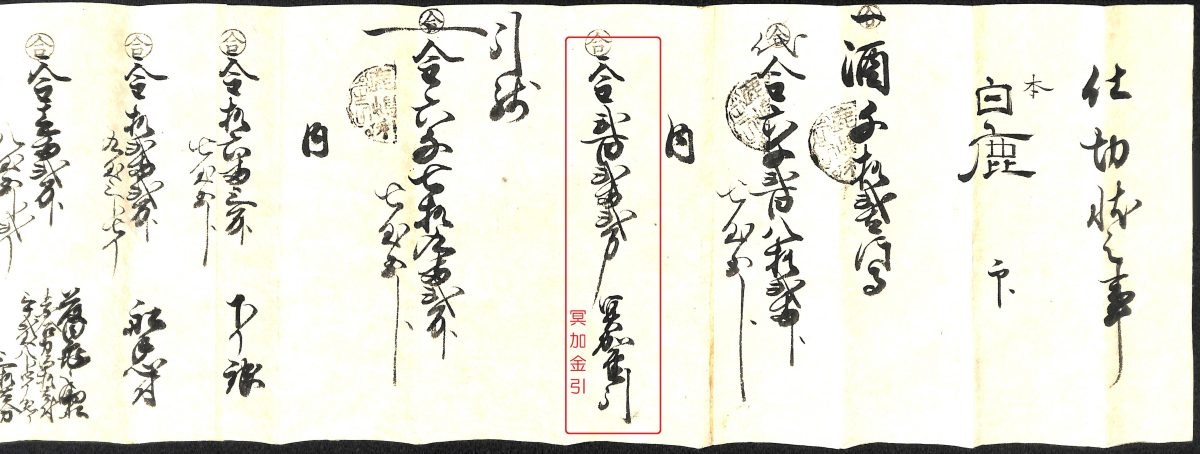

The most infamous sake tax of the Edo period was called “sake unjo” imposed in 1697. This tax system from the Edo shogunate increased the selling price of sake by an unbelievable rate of 50%, and the shogunate collected the entire increase as taxes. For example, the sake originally sold at 100 monme of silver was raised to 150 monme, and the increased 50 monme was collected as taxes. Furthermore, the shogunate adopted a policy of curbing the amount of sake produced, resulting in higher prices for sake and a decrease in production. Gradually the revenue from “sake unjo” tax decreased, and this system was abolished in 1709. It is believed that the abolition of this tax was due in part to the production of illicitly brewed sake during this period.

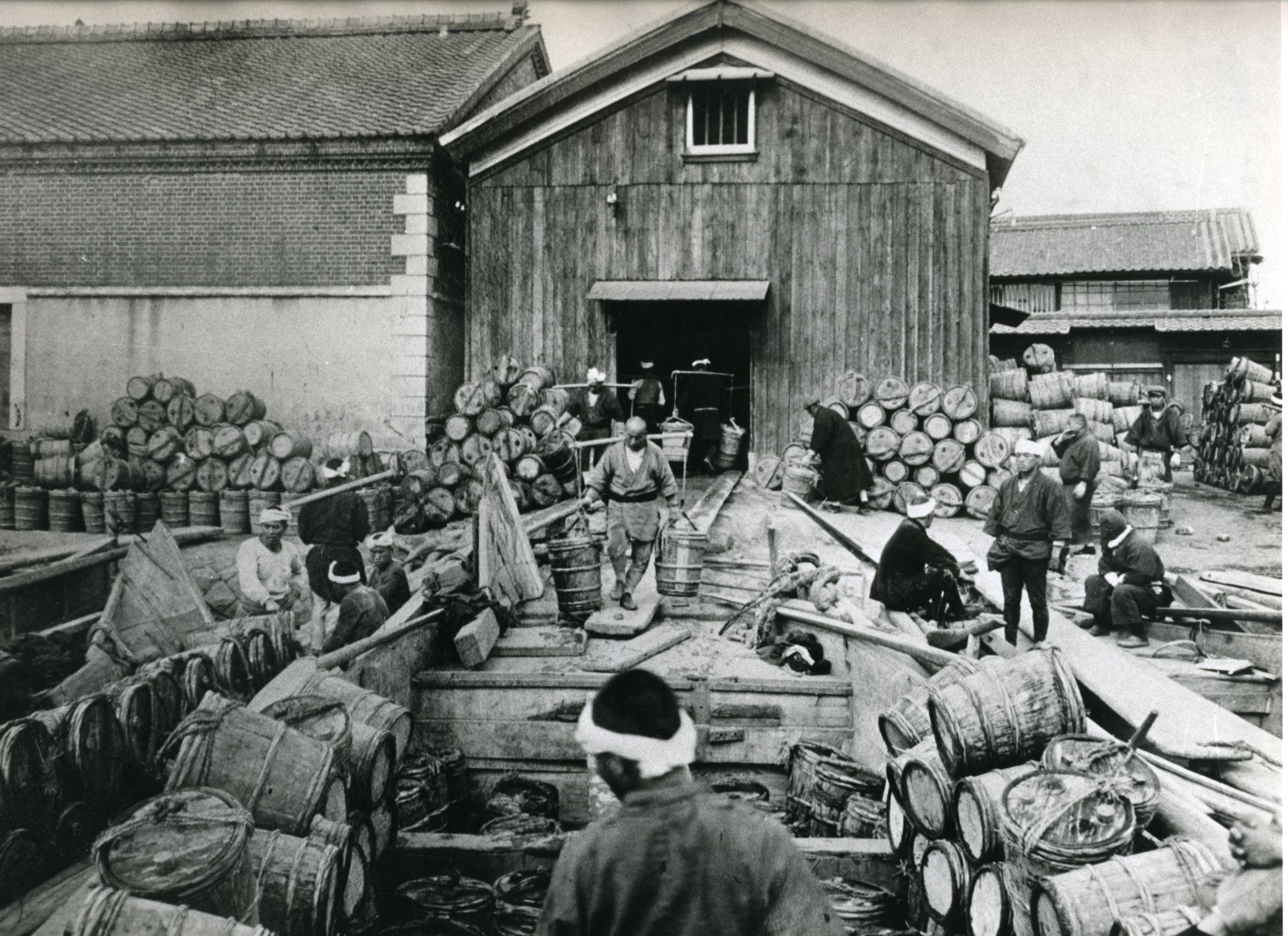

The additional taxes imposed on sake also impacted the sake brewing industry in Kamigata (Kyoto and the surrounding vicinity where the Emperors resided). Towards the end of the end of the Edo period, a surcharge of 6 monme of silver per barrel was imposed on sake wholesalers in Edo. These sake wholesalers then charged the sake brewers in Kamigata for the cost of this additional tax, resulting in conflict between the wholesalers and the sake brewers.

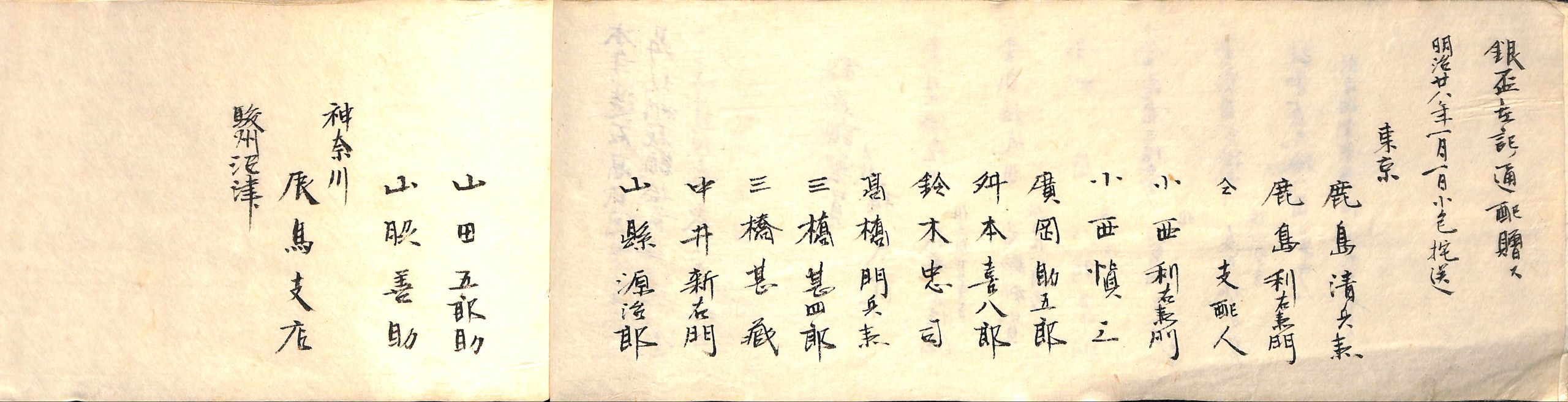

During the Meiji era (1868-1912), sake tax became an important source of revenue for the government. The rate of sake tax gradually increased, and the share of sake tax in the national tax base grew accordingly. In 1899 (Meiji 32), the share rose to 35.5% of national tax revenues, overtaking land taxes to become the highest tax revenue source. Later, land tax revenues again temporarily outpaced sake tax revenues, but from 1909 sake tax revenue again rose to the highest share, until it was overtaken by income tax revenues in 1918.

The current liquor tax rate has decreased to 1.7% (1.1 trillion yen as of the 2020 fiscal year), and the percentage of tax on sake within the liquor tax has also decreased to 4% (45.1 billion yen). This is because the sake industry has been stagnant and is reportedly shrinking in recent years, while other industries have been growing due to modernization since the Meiji era. Our hope is that the reduction in the sake tax rate beginning this October will revitalize the sake industry once again. We hope our readers will continue to enjoy sake in moderation, and support the sake industry.

The key to nationwide expansion of sake sales lies with authorized dealers!